Guest author and outdoor guide Tristan Reid gives his take on how Victoria’s climbing bans fit into a much larger government push for “reconciliation” via Aboriginal corporations. This article is a good place to start if you don’t know the background behind the government push to move public land away from the public and into corporate control.

The latest blanket climbing bans under a “Recognition and Settlement Agreement” (RSA), shows the long march through the institutions is reaching its culmination. All public land access is at threat.

Australia’s Mount Arapiles, in south-western Victoria, is known as the “best crag in the world”. For the quality of the rock, the climbs, proximity of camping spaces, and natural prowess. It has welcomed international climbing royalty down to “bumblys” – beginners of the sport. Every April, as the hot climate cools, climbers descend on Arapiles from all corners of the globe. Low estimates put the number of visitors at 51,000 people in 2018. The small town of Natimuk, fed and expanded by climbing pilgrims since opening up to climbers has boomed. “Crag Care” volunteers have helped maintain Arapiles-Tooan State Park for decades. This shared history is passed down through written records, folklore, climbing mentorship and fraternities. For the secular outdoors enthusiast, it is sacred.

Legendary climbing achievements were forged on the prominent cliff. The first climbs up the steep faces occurred in the 1960s; by the mid 1980s the then hardest rock climbs in the world were established. In 1985 “Punks in the Gym” was completed for the first time by German Wolfgang Gullich, one of the most influential climbers in history. It would take 10 more years for any Australian climber to repeat.

With these highs are the tales of low. In the late 1980s, cases of scurvy were reported amongst several “dirtbag” climbers, a vagrant climbing tragic. This Dickensian ailment owed to their appalling diet, largely consisting of stews gleaned from farm scraps. Legend even suggests canned dog food was in the mix. The Australian adventurer John Muir miraculously survived being struck by a falling two-ton rock, which was moved to the main campground where it remains today. Now this chapter of outdoor history is coming to an abrupt, forced close.

Before this recent history it was that of the clans of the Jadawadjali Aboriginal language group. 37 clans, with estimates of 2000-4000 people, lived in the region. With the earliest radio-carbon dating going back 5170 years at Mt Talbort in the south-east. The first known European contact was in 1836 and by the late 1840s most Aboriginals had been displaced. Variously killed by disease, poisoned by alcohol or massacred, with the Wimmera River massacre the most infamous of the killings. The survivors eked out a living, working on stations, or surviving on post-dispossession charity, with others relocated to the Ebenezer Misson, to the North at Antwerp.

In 1992 forty-two locations were surveyed in one of the first major archaeological surveys in the area. It recorded rock art, scar trees, quarry sites and ceremonial areas. Some of these were at Mount Arapiles. In 2005, Native Title of the Wotjobaluk Peoples was recognized, granting fishing, hunting and camping rights in the region, with freehold land granted in a few select areas in Wimmera and Southern Mallee. Funding was provided for the establishment of Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation (BGLC) who would also co-manage public parks.

In 2010 Victoria passed the Traditional Owner Settlement Act, which was created to accelerate reconciliation goals by negotiating Recognition and Settlement Agreements (RSA). This act is variously described as a, “means of court settlement of native title and delivery of land justice in Victoria”, which facilitate “[i]ncreased economic, social opportunities, partnerships, strengthening communications and cultural identity.” It bypasses adjudication on Native Title in the Federal Court by directly entering into agreements with the Land Councils. The Act also created a new freehold Aboriginal Title, applicable on public lands where heritage has been identified. On 25 October 2022, the Victorian Government and BGLC, signed agreements under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic) and related legislation.

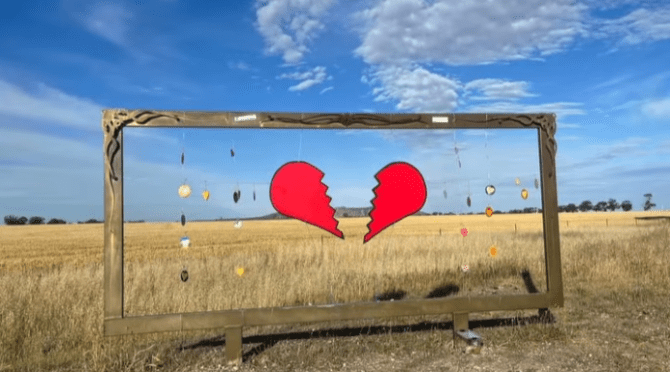

On Monday November 4th at 5pm (the day before the Melbourne Cup public holiday) Parks Victoria announced the Dyurrite Cultural Landscape Management Plan Amendment. The secretive multi-year plan is the culmination of a 2022 RSA, negotiated with Barengi Gadjin Land Council. The plan declares that 63% of the current climbs, the majority of the high quality classic routes, climbing festivals, events, and off-track walking are to be banned immediately. Feedback was only open for 28 days. Public assurances from both the Government and BGLC that the RSA would not affect existing rights or access have been revealed as a lie. The news was received by the climbing community, and all the people reliant on climbing tourism for their livelihoods, as a bitter betrayal.

Parks Victoria facilitated a single, carefully managed online community engagement session on the 13th of November. All questions were required to be sent ahead of time. Submissions regarding the plan could be made online but Parks Victoria also announced that submissions would not change the bans in any form. A message reads, “[w]e welcome feedback from the community about changes to the management plan … the areas that need to be protected will not change.” If anything can be said about the process it was refreshingly honest to publicly state that feedback wouldn’t be considered at all.

Arapiles draws over 50,000 annual visitors supporting a $12 million dollar tourism industry. To whom the adjacent town of Natimuk may appeal, to simply state their concerns, is unknown. The population of 514 residents (2016 census), small-businesses, gear manufacturers, climbers, guiding companies, bush care volunteers and tourism supporting industries, have been treated with callous disregard. They butt up against a perfect closed system of unaccountability. The Government defers to Parks Victoria, Parks Victoria defers to legislation and the BGLC doesn’t publicly engage at all. The impact the plan would have on the region was never considered. Developments for Indigenous Cultural tourism are however, at the fore of the new Plan of Management.

Arapiles was not the first major closure in the State. Another event, the oldest off-road racing event in Australia, The Mallee Rally, has been cancelled since 2018. Having met at Lake Tyrrell for the previous 46 years, a “permit to harm” application for their 2019 race was withheld. Subsequently a new draft Cultural Management Plan was released. Submissions responding to the draft were put forward but all attempts to discuss the plan directly with Parks Victoria and the local Land Council, the BGLC, were rebuffed. Plans for alternative race routes on public land were ignored. The final report is yet to be released. To date, the process has lagged for five years.

The race was ostensibly banned due to proximity to Indigenous artifacts and environmental impacts from the racetrack itself. However, apparent concerns over human impact did not stop concurrent tourism developments at the lake. New tourist infrastructure including a traffic flow upgrade, an upgraded car park, the “Sky Lounge” viewing platform and upgraded visitor centre have all been added since the ban.

Nowhere has the closure of public land, in the name of heritage protection, followed by new commercial developments, been more pronounced than in the Grampians. The Greater Gariwerd Landscape Management Plan 2019 was the first major blow to Australian climbing. The draft management Plan was scandal-plagued from the start.

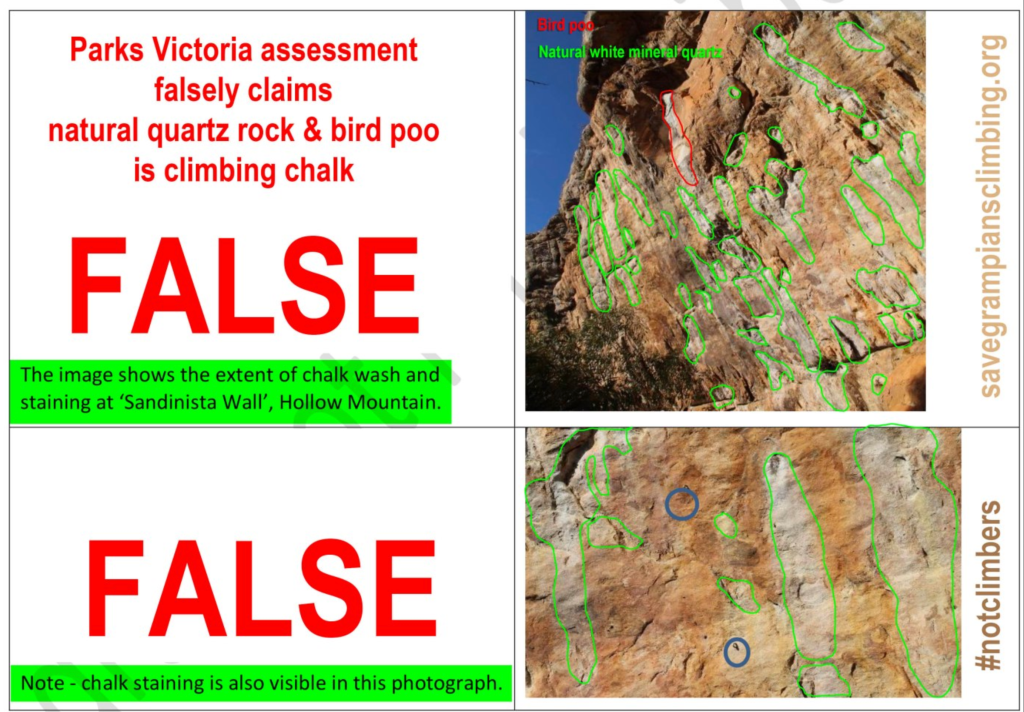

Without any evidence, graffiti found in non-climbing areas was blamed on climbers. Cultural Surveys undertaken by alleged experts misidentified bird droppings and naturally occurring coloured mineral deposits, visible on rock faces, as climber’s chalk. Most infamous were pictures distributed by Parks Victoria of bolts and drill-holes, carelessly placed in high-quality indigenous rock art, which too was blamed on climbers. It was soon revealed that the offending bolts were in fact part of a Parks Victoria safety installation built to protect the rock art. Despite the groundless accusations no official correction was ever offered. An updated plan inserted the word “apparent” before “chalk wash and staining”. This Plan was implemented in full and 79% of the climbing areas are now banned.

Most controversially, a core part of the plan included the announcement of the “Grampians Peaks Trail”. It was a new 160km fee-paying bushwalk, developed in conjunction with three of the local Land Councils, bulldozed through large sections of untouched bush. The co-management plan necessitated the removal of 14.4ha of native vegetation for tracks and accompanying infrastructure: 12.1ha for 97.5km new walking track, 0.3ha for 1.62km vehicle access tracks, 0.9ha for 11 new hiker camps, 1.1ha for 5 new trailheads, extension to 5 existing trailheads, 1290m² vegetation clearing for 138 new car parks, widening of existing tracks (the impact of widening on vegetation was left uncalculated), the installation metal bridges, bolts, walkways, and finally tree work and trimming to keep the new track clear of falling debris. In answering rhetorical questions on a FAQ sheet, Parks Victoria deemed this “not significant” damage.

Facing the initial closures in the Grampians, climbers attempted to organise a representative body to advocate for their rights. This immediately descended into a war of denunciation. Potential leaders, critical of the plans, were castigated as racists. Instead of selecting fearless climbing advocates, the chosen representatives were selected on the basis of servility to cultural concerns. The model of advocacy that followed would be a chimaera of climbing and indigenous advocacy, ultimately revealed by the Arapiles ban to be at cross purposes.

One such group was the Gariwerd Wimmera Reconciliation Network (GWRN). The landing page of their website expresses a desire to “share country” and “great sorrow at the cost of that sharing”. With $4300 of grants from local councils they developed videos and materials invoking all the essential virtue signaling placards: “How to be an anti-racist ally”, equity, truth telling, sharing country, “getting educated”, “walking together”, and so on.

An enthusiastic forward-looking newsletter in 2021 reported on, “the opportunity to talk respectfully … about digesting changes in the governance of Country…. and what it means for climbing and for our identity as climbers”. More recent announcements in response to the Arapiles climbing bans are notably less enthusiastic. Calls for “restraint from hurtful or antagonistic dialogue and behavior” and to “be mindful of the wellbeing of others as well as yourself”, denote a distinct change in tone, suggesting that the dual mandate is an increasingly difficult meal to digest, even for the staunchest of allies.

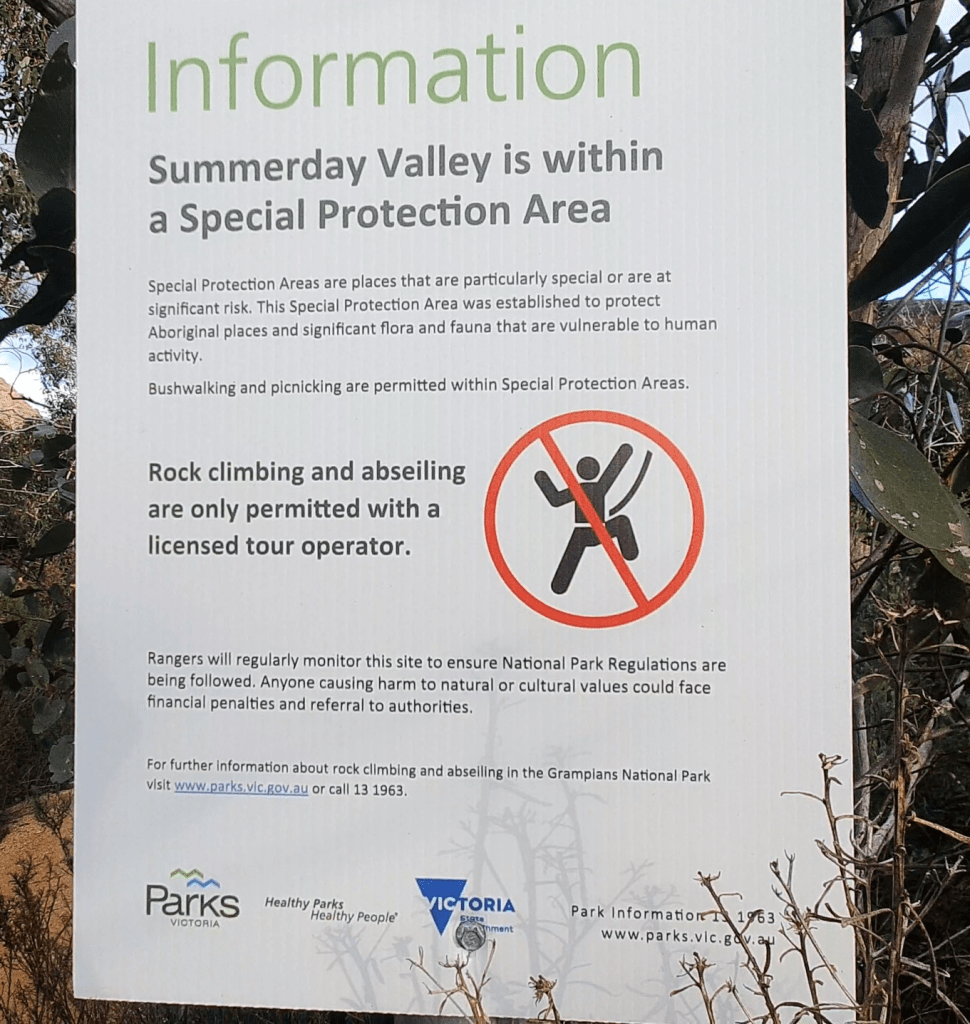

While Land Councils can ignore the pleas of the public they have the power to crush and exclude dissenting stakeholders. For 20 years Tori Dunn ran a successful guiding company in the Grampians. The 2019 new management plan came with new licensing conditions for tourism operators. The licensing agreement required operators to attend mandatory cultural education as well as signing a “permission to harm” permit. The crux of these agreements requires agreeing to the terms, “To carry out an activity that will, or is likely to, harm Aboriginal cultural heritage”. This self-flagellating exercise, admitting to cultural harm or the potential to cause it, costs $681.

What harm to cultural sites that might have previously occurred is not known, as no concrete examples were never provided. The Grampians, Summerday Valley Application details that, “Traditional Owners have raised concerns with Parks Victoria on the impacts that recreational activities, including climbing, have and continue to have on tangible and intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage in the Summerday Valley area”.

Alleged examples of harm included, “chalk on rock face” (not on cultural sites), “potential rock fall damaging quarry sites”, “walking tracks disturbing soil” and harm to “intangible heritage” from humans “physical access of areas…where it is possible that harm will or is likely to occur”. Outdoors enthusiasts have been walking, scrambling and climbing in the Grampians since the 1890s. Such middling examples of “harm” would have once been considered a triumph of the ethos of minimal impact. Understanding the relationship between heritage and harm, as written in law, is essential.

Cultural heritage, intangible heritage and harm are defined in the 2006 Aboriginal Heritage Act. Cultural heritage pertains to Aboriginal places, objects and remains. Intangible heritage relates to any knowledge (stories, rituals, practices, etc) or means other than cultural heritage. Harm is defined as damage, defacing, desecrating, destroying, disturbing, injuring or interfering with cultural heritage. Consideration for the rights of other stakeholders, in any of the Acts, is non-existent.

Tori Dunn made her concerns and disagreements about the plans known, numerous interviews and articles can be found online. The local Land Council publicly raised objections about Dunn’s stance. Dunn, not wanting to sign the agreement and accept the imputation that climbing was “causing harm”, was publicly banned from guiding by Parks Victoria. Facing the choice of exile or accepting the overturning of the presumption of innocence by agreeing to the imputations, Dunn closed her business of twenty years.

Other operators have accepted the terms of the agreements- one company manager wrote in a climbing forum, “I signed with gnashing teeth, cognisant that I represent 150 fellow employees in my company…knowing that otherwise many kids would miss out on the opportunity to climb here…too many people are scared of losing their job”. A permit system, with mandatory Indigenous cultural education, has been proposed for the remaining public areas but has not yet been delivered.

Compulsory re-education programs have not been limited to climbers. Public land hunting has a deep historic, cultural and institutional history in Victoria. Duck hunting narrowly avoided an outright ban in 2023, pushed by the Animal Justice Party Victoria. The Government confirmed that the activity would continue but with updated terms and conditions. Mandatory cultural heritage training will soon be required for hunting license applications; of which there were 58,000 licenses in Victoria in 2024. This surprising adjunct emerged from nowhere, but it is undoubtedly part of a trend of multi domain re-education campaigns.

Recent reportage detailed that Victorian Justice Department Workers will be offered “voluntary” White Privilege Training. The training is said to be an essential part of the push towards Victoria’s Treaty negotiations. When concerns were raised about the racialised program, Corrections and Youth Justice Minister Enver Erdogan publicly backed the training module. He conceded that a name change may have been prudent. “[It] probably could have been rebranded,” he said. The issue was not the content or existence of race based, unscientific, political re-education programs for government workers. The issue was that people noticed.

No more damning insight into the political calculus of these efforts can be provided for by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council itself. Explaining the reasoning behind the initial Grampians ban the Annual Report 2020 states, “[i]f signed off, this will bring the focus of places like the Grampians back to Culture, rather than simply recreational”. For the new wave of progressive activists ‘simple recreation’ is heresy as it lacks the adequate deference to Aboriginal metaphysics. It is not enough progress to simply prescribe physical barriers around artifacts or sites but one must acknowledge the absolute primacy of “Culture”. On Victoria’s formerly public lands, norms are now set and policed by Land Councils.

Less apparent are the financial arrangements and the political ambitions of Land Councils. The funding agreements of the BLGC’s RSA are publicly redacted, but the ORIC financial records provide ample detail. In 2023 of $7.5 million revenue, $6.8 million was provided from State and Commonwealth grants and only $700,000 derived from “fees for service”. The publicly listed services on the BGLC’s webpage are, “Traditional Welcome to Country Ceremony” and “Combined Welcome and Smoking Ceremony”. Total net revenue was $2.5 million, with a hefty $9.6 million cash account, contributing to a combined total of $12 million of assets. The total net equity of the BGLC was $6.5 million, with revenue quadrupling and net equity increasing by 70% from 2022. These vast resources fund the BGLC’s 31 employees averaging $93,656 per person.

Despite the rivers of public funded revenue, while holding large cash reserves, additional funding flowed via the RSA. This included the first instalment of $6.1 million to Victorian Traditional Owners Trust (VTOT), from which a minimum of $312,00 will be paid to the BGLC annually for the next 20 years. A $1.6 million infrastructure package to facilitate “cultural tourism” at Arapiles, additional funding for rangers, a new Traditional Owner Land Management Board, transferral of sensitive Crown Land and the de facto ownership of Arapiles, held as Aboriginal Title.

The generous financial agreements are enabled by the smallest part of the Settlement Act 2010. At a mere 75 of the 25,491 word act, Funding Agreements (Part 5, Section 78.). reads: (1)“The Minister… may enter into an agreement with a traditional owner group entity …as to the provision of funding to the entity for the purpose of giving effect to the recognition and settlement agreement… (2) An agreement under subsection (1) may provide for money to be paid to a charitable trust approved by the Minister.” The BGLC’s 2023 financial report evinces that this legislation does not merely resemble a blank check, but it is being used as one.

Unsatiated with vast sums of public finance and land arrangements the BGLC has designs on local government. The 2022 RSA section “Local Government Engagement”, Proposed Actions sections A-H includes: “Consulting on renaming local roads, public spaces, flag flying protocols…and payment of fees for this service. Developing and delivering education programs for councillors, council staff and the broader community. Engagement in strategic planning, incorporating self-determination into council planning, ensuring rights, aspirations and perspectives are considered by the local council. Periodical reviews of law…consulting on strategic planning. Council to preferentially source goods, services, management of council lands and employment plans. Local government funding is to be set aside to implement these proposals”.

This is power with no responsibility, and few mechanisms of accountability. Land Councils are a culturally protected quangocracy. Attempts to examine or oppose them can be dismissed with the claim of cultural insensitivity or racism. The current arrangements and stated aspirations cut against the grain of Australian political culture. That is one that broadly aspires for pluralism, fairness and equality. Victoria is instead pursuing “equity”, redistributive justice, where societal shares are forcibly reallocated towards historically marginalised groups.

It is abundantly clear that some Victorians are now waking up to the realisation ‘the long march’ has permeated through every level of culture, every private and public institution. Some became the willing, unwitting, vassals of ideology. Seeking to achieve “critical consciousness”, they sought atonement for their supposed sins by adopting the yoke of the interloper, given full expression in the mantra “climbing on stolen land.” For the reformers, public declarations of their clearly doctrinaire intentions belie their confidence in their total and continued institutional control.

Every Victorian is affected. State Forests are being rezoned as National Parks with greater co-management planning at the core. Restrictions on horse riding, dog walking, bike riding, 4W Driving, hunting, prospecting and off track bushwalking. Compliance is achieved with trail closures, locked gates, boulders rolled onto fire trails, hidden cameras and signposted threats of enforcement. Harassment from rangers both in the bush and at private residences have been reported. Parked cars are photographed at trailheads in order to question people at home about their prior outdoor activities. In 2021 a list of recommendations, aimed at bolstering heritage enforcement, the Heritage Council sought powers to enter private premises without consent, as well as the power to exile individuals and organisations from public land for up to 10 years. Other Australians must pay heed, the Victorian example could set a precedent for lockouts elsewhere.

If pursuing equity is inimical to equality what is to be done? Cultural artefacts and heritage absolutely need protection. The solution is staring us in the face. That recent heritage could be “rediscovered”, in high use areas, owes to the deep reverence held towards ancient signs of passage. A century of evolving recreational pursuits, in these wild places, has barely produced any tangible evidence of physical harm, desecration or destruction. The very survival of cultural heritage has often owed to the voluntary efforts of non-Indigenous Australians in marking them out for preservation.

No explanation of how any of the banned activities were interfering upon cultural practice has ever been offered. It was simply declared that it did. Tangible heritage can be protected from direct physical damage but when cultural significance is found in the realm of the intangible, where can the bounds of harm be possibly drawn?

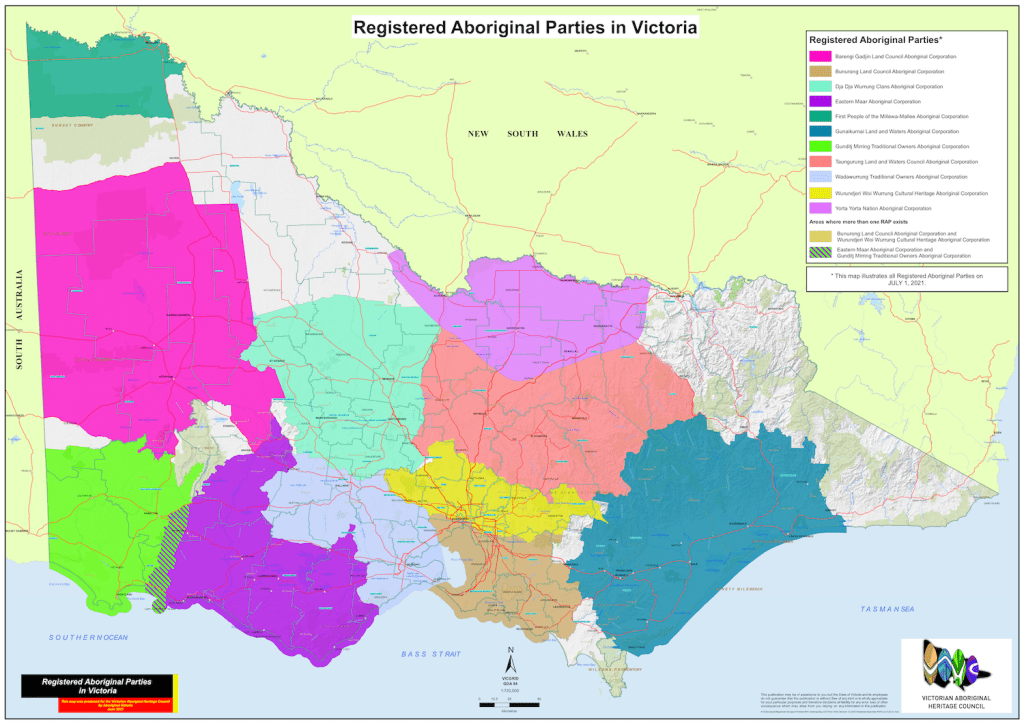

Registered Aboriginal Parties cover 75% of all land in Victoria. The initial Grampians’ closures started with 54% of available climbs closed, now it’s 79%. The closures at Arapiles were initially in a single location, Declaration Crag (Taylor’s Rocks). Parks Victoria noted, “[o]ver time, as assessments reveal more details of Victoria’s incredible cultural history, we will look at whether new park management strategies are required to protect and preserve them.” The expansionary remit is explicit. What’s at stake is not merely access to outdoor locations and activity rights but Reconciliation itself. The entire project was left teetering in the wake of the Voice Referendum. Singularly minded activist groups, with the support of a myopic and ideologically blinkered State government, risks shattering it entirely.

SGC Editorial Independence

We cop quite a bit of criticism on this blog for not being “positive” enough about the current events. Apparently we are supposed to be following the rule of say nice things or say nothing at all. Sorry that is not going to happen. Don’t visit this site if you only want to read feel good puff pieces. We will always keep publishing documents, quotes and whatever we can get our hands on from a myriad of sources. We will continue to question relentlessly any decisions made that effects the rock climbing community. We are fiercely independent of any climbing access organisation, club or government department so we can be an equal opportunity critic. We will not be shying away from acknowledgement of losses to the climbing community. We will publish the climbing history and context of banned climbing areas. We will not be burning the history books and pretending it didn’t happen. Hypocrisy has no place here. If someone puts themselves forward in the public eye as an expert then we expect that to be backed up by facts. Sometimes truth hurts and can be uncomfortable. Ruffling feathers and making people want to research further to be better informed is the aim here. Don’t take what we write here as gospel – do your own research and make your own informed decisions. Talk about this with your friends and your enemies. If you have better information then let us know – we are happy to correct factual errors and do it regularly when better information is presented. Or even better publish your own! We have published over 100 articles on Victorian climbing bans over the last 5 years. We really would prefer to be doing something else like climbing…

Case study: Ganguddy- Dunns Swamp

Interested on how other States are handling the issue of balancing protecting art sites and allowing recreational users? Take a look at this simple case study from NSW where Cultural Heritage is honored without wholesale restrictions on public access.

Very interesting read. Just another gravy train, where tax payer money gets squandered on rather dubious projects with 0 outcome.

LikeLike

Non inclusive Government policy and thoughtless over regulation that uses tax payers money for no gain. The damage and loss of tourism and business investment in Victoria will be substantial, and is already being noticed, as people move to other states. Why are we being made to feel guilty instead of being encouraged to responsibly enjoy our natural resources.

LikeLike