Wondered how other jurisdictions protect Aboriginal cultural heritage whilst continuing to allow public use of land for recreation? We recently visited an excellent example in the Blue Mountains, New South Wales.

Case Study: Ganguddy-Dunns Swamp campground – Wollemi National Park, NSW

The quick hit? A popular camping and rock scrambling area combines harmoniously with Aboriginal cultural heritage.

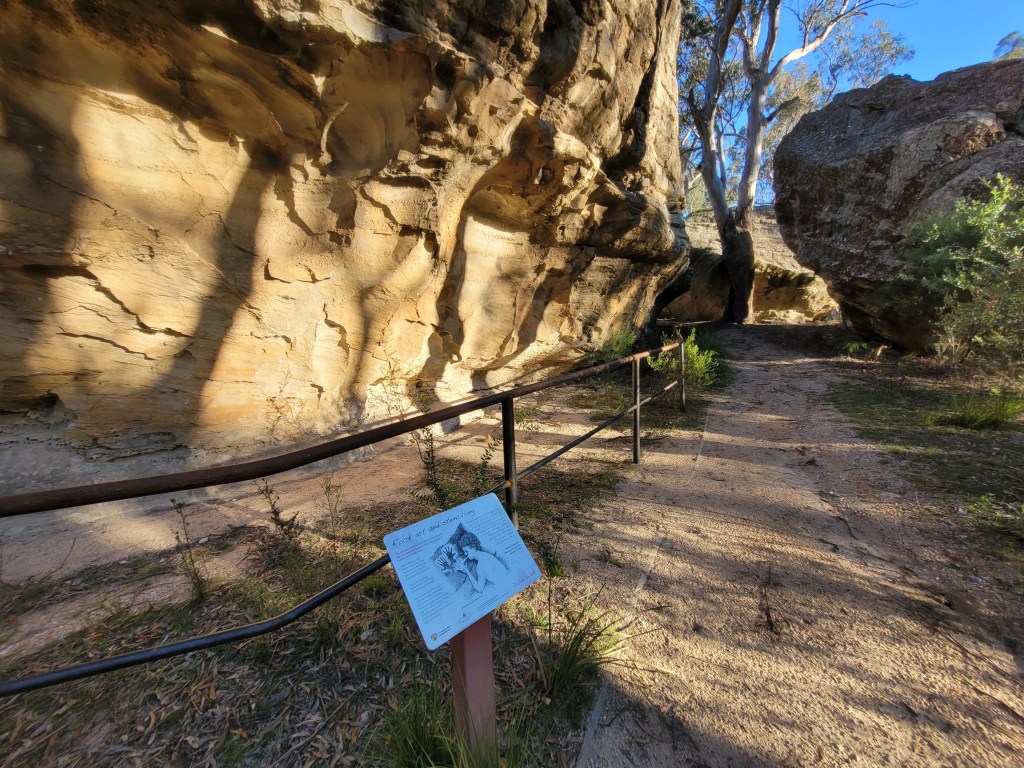

This well visited campground – with over 70 bookable sites – is based around a series of sandstone rock pagodas and a well used waterway for kayakers. In peak holiday periods there would be hundreds of visitors to this campground per day. Two sign-posted Wiradjuri rock art sites exist in the campground area within metres of formal walking tracks, formal campsites and rock pagados used by visitors for scrambling, views and bird watching.

The rock pagodas create a labyrinth of summits, walls and ridges that are an obvious and popular unroped climbing challenge for visitors (mostly children). At sunset there can often be dozens of children scrambling up these rock walls. These scrambles are metres away from the two Aboriginal rock sites.

One formal campsite consists of a rock shelter you can camp in and a firepit.

There is no visible ranger presence at the campground – and no nearby visitor center etc. There is no signage prohibiting rock scrambling in the park.

Rock art sites

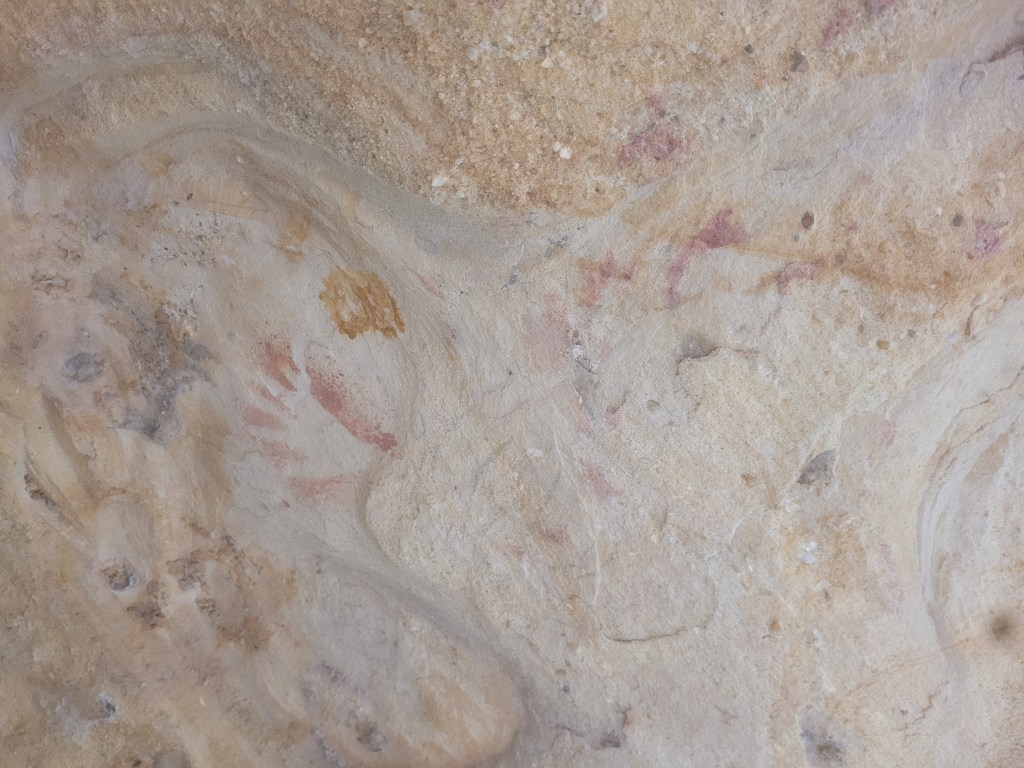

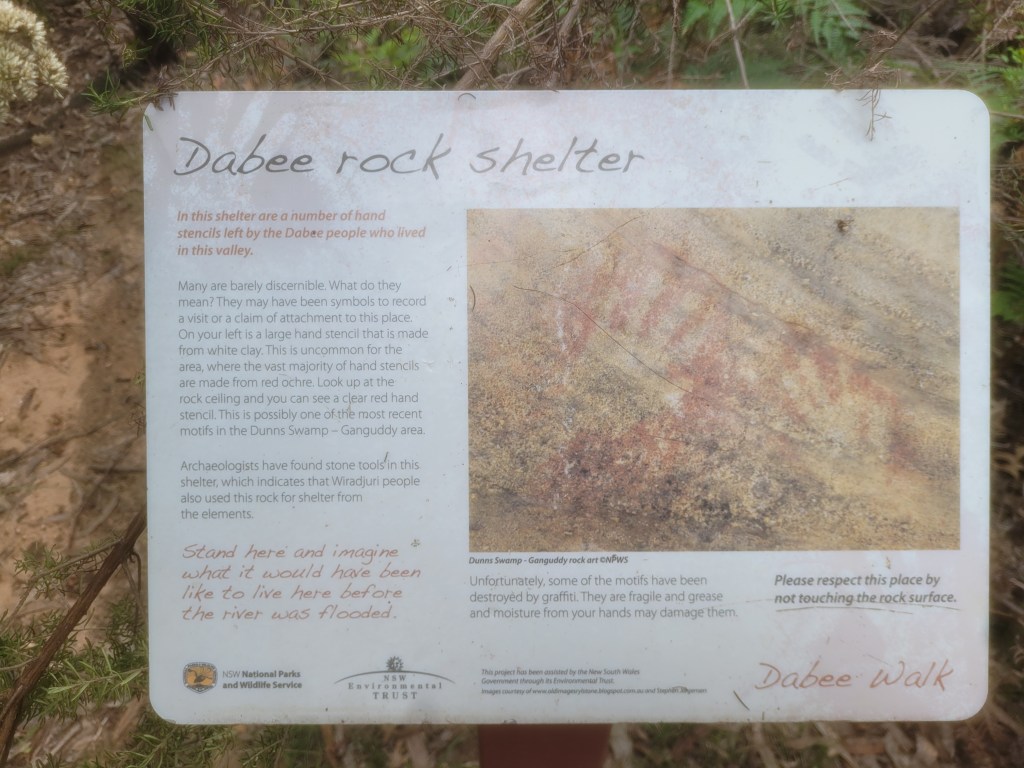

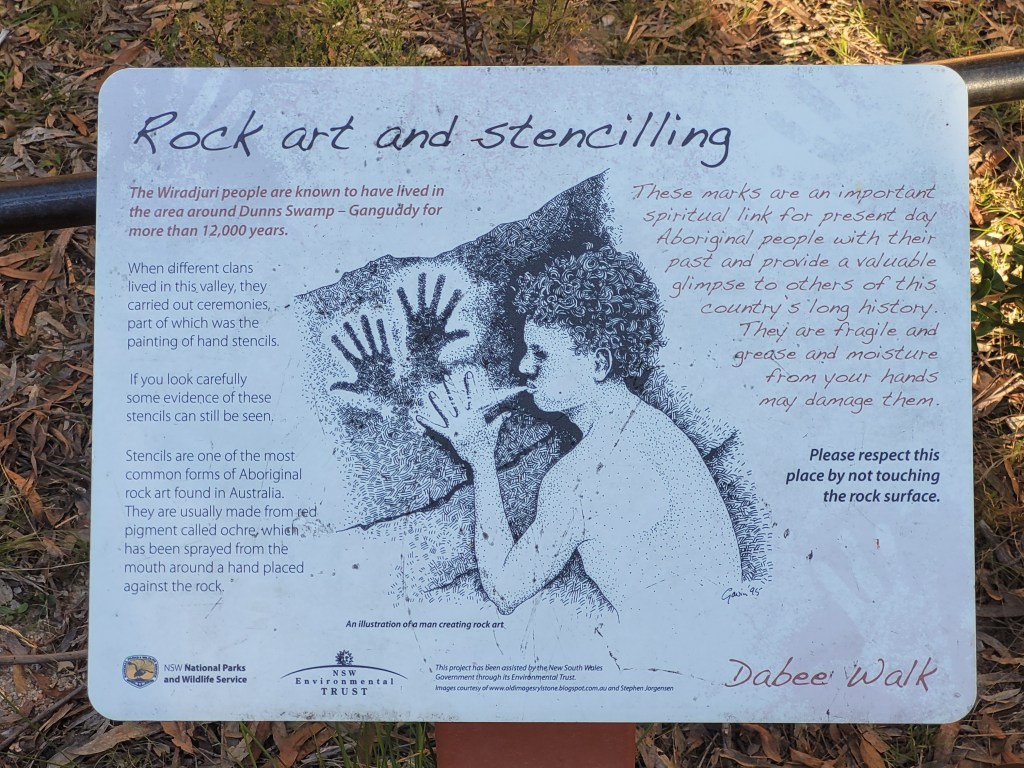

The two sign posted cultural heritage sites in the campground consist of low overhung caves with faintly visible hand prints of red and white ochre. Signage also mentions the existence of stone tools being located in one of the caves.

Both sites are sign-posted with small interpretive metal signs.

One site has a knee high wooden railing about 2m across and the second site has a waist high metal railing about 10m across. Both fences are not high enough to stop people crossing them if they wanted to. They are designed to separate the walkers from the rock shelters in a clear way.

The caves containing Aboriginal rock art are free of graffiti and other deliberate damage despite there being no physical barriers to stop vandalism.

From our observation many visitors to the campground enjoyed looking at the art and reading the signs as part of their visit to the campground.

If you walk further into the bush surrounding the campground it is possible to find other Aboriginal rock art sites which are neither sign posted or fenced. They remain in excellent condition despite hundreds of visitors.

On our visit there was a small party of what appeared to be Indigenous land care workers doing weeding work along the foreshore. We offered to help them and they welcomed our assistance. There appeared to be no concerns with the kids climbing on nearby rocks. We shared some knowledge on invasive weeds and wished them well for the rest of the day.

Our impression was an area that allowed shared use of the rocks for recreation whilst also honouring the existence of cultural heritage. We think this could work at Victorian climbing areas such as Arapiles State Park and the Grampians National Park rather than closing large areas to all visitors as is planned by Parks Victoria.