If you have been following along on the five+ years that Grampians/Gariwerd and Arapiles/Dyurrite climbing bans have been slowly ratcheting up you will have undoubtedly come across “quarrying” as one of the reasons for area closures. This article will outline how “protecting” these quarries is a major reason for climbing closures in Victoria and that the reasoning behind the bans is highly flawed – rock climbing does not fundamentally harm these sites and both can mutually co-exit as they have done for many decades so far.

- Stone tool quarries are the reason many climbing areas are being closed – not rock art sites or sacred sites.

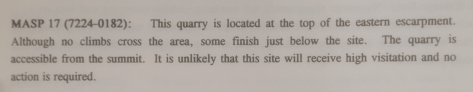

- Archeological report from 1992 says that stone tool quarries are almost immune to harm due to being made of rock and that “no action is required” to protect them from climbers.

- The only harmed stone tool quarry at Arapiles is from someone shooting bullets into it prior to the area being used for climbing.

- Poor mapping by the general public on the thecrag.com have created unnecessary climbing bans.

- Other States aren’t banning public access to public land due to rock quarrying.

Why do we need to talk about this?

We have been warned not to talk about this. “It’s their heritage – they can do what they like” “You cannot question the assessment process” and so on.

Yet – people are talking about it behind the scenes or in round about ways. It’s the elephant in the room, with just a nod every now and then in some people’s passionate letters to parliamentarians and land managers.

“Climbing and Cultural Heritage can co-exist, we can all get along”

They mean quarrying.

When Climbing Victoria says in a statement: “Climbing Victoria are keen to work with BGLC to continue to find solutions so that climbing and the preservation of cultural heritage can co-exist in harmony”.

They (primarily) mean quarrying.

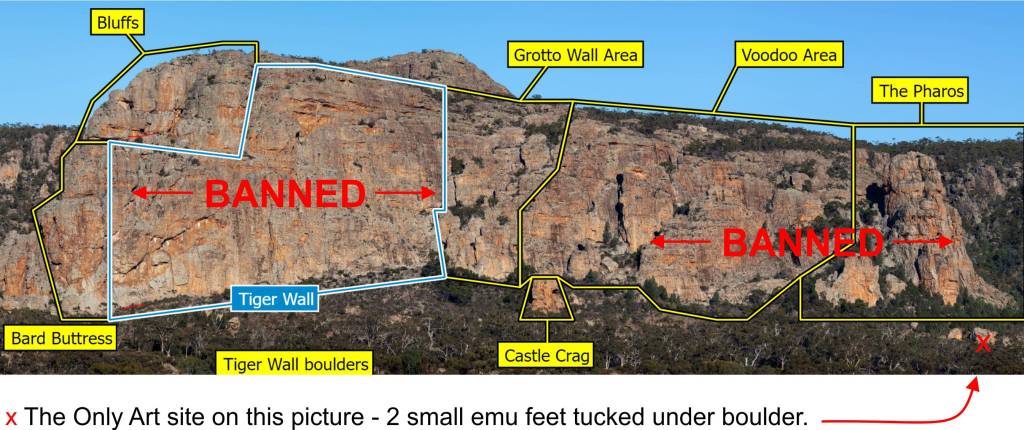

They don’t mean rock art (invisible or not), as it is now well known that the half a dozen artwork sites (at Arapiles) are minor, and very tucked away – with no artwork at all on the main cliffs slated to be banned (Tiger Wall, Pharos & Tiptoe Ridge etc). Climbers understand that rock art is rare, delicate and unique and requires protection.

However the parliamentarians don’t know that areas are being closed because of the activity being in proximity of rock quarrying; the public and (most of the) media also don’t. In their minds, they imagine climbers drilling into rock art, and climbing over vast and spectacular sacred sites. When the reality is hundreds of metres (horizontally and vertically) of cliffs are being taken completely off-line because of the existence of rock scarring and loose rock chips at ground level – often tucked away from people under a bulge. No where else in the world bans all access to the general public in huge areas because of rock quarrying.

What areas are closed because of quarrying?

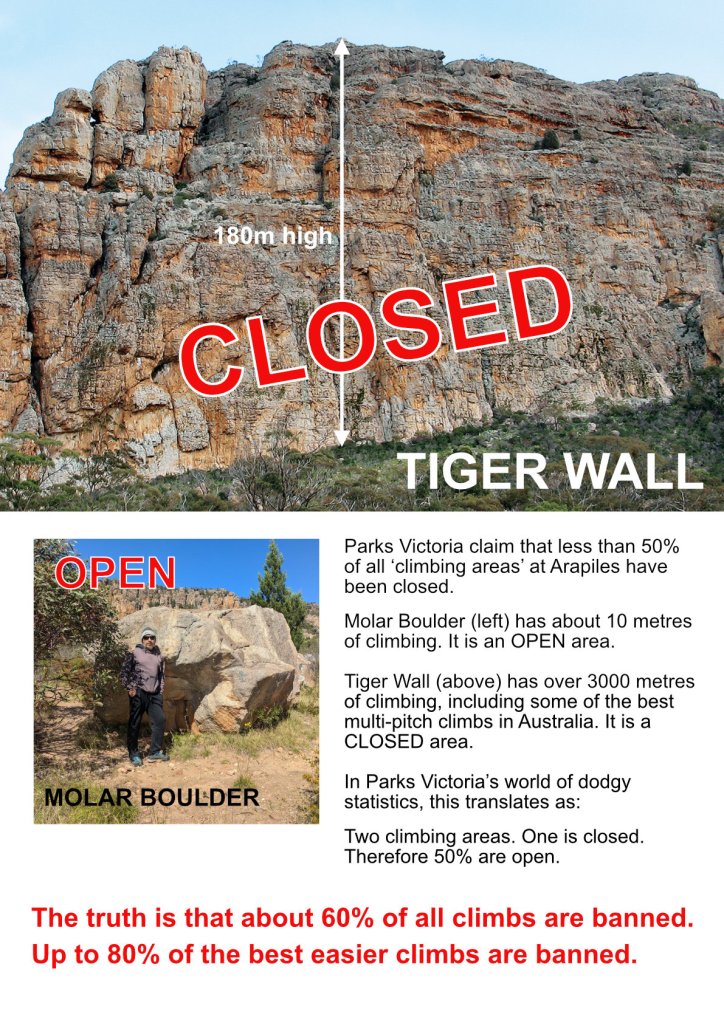

We can’t be certain because the most recent detailed archeological surveys are not on the public record, but we have a pretty good idea quarrying is the reason for the complete closures of major internationally significant climbing areas such as Tiger Wall, The Pharos, The Bluffs and in the Grampians – Summerday Valley, half of Taipan Wall, Spurt Wall, Muline, Snake Pit, half of Bundaleer, Clicke Wall / Bouldering, The Tower, Plaza Strip, the Gallery, Hollow Mountain Cave and Gilhams Crag just to name a few. And remember because Parks Victoria closes complete climbing “areas” rather than individual climbs – a couple of centimeters of rock scars at ground level can equal the closure of a hundred metre wall containing hundreds of climbing routes.

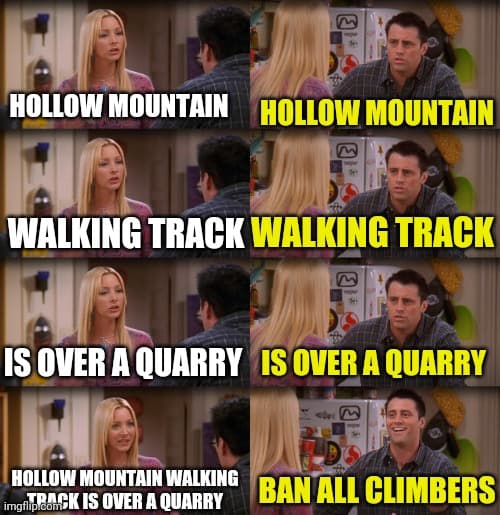

It should be noted that closures of tourist walking tracks has not occurred because of the existence of Aboriginal quarrying despite much evidence that walkers/scramblers present an equal (or potentially greater?) threat to these sites as do rock climbers. There are many examples of tourist tracks along which such harm is evident and these tracks have not been closed. Double standards PV? You can read more about this hypocritical stance from PV here in our article from 2020 – where tourists are more likely Hollow Words – PV Ignores Tourist Damage at Aboriginal Site.

What are Aboriginal quarries?

From the the Victorian Government’s First People’s State Relations Fact Sheet:

Aboriginal quarries are places where Aboriginal people took stone from rocky outcrops to make chipped or ground stone tools for many different purposes.

- the rock is a type that can be made into stone tools, such as greenstone, silcrete and quartzite [Arapiles]

- the outcrop bears scars from flaking, crushing and battering

- pits and trenches are found around the base of the outcrop

- large amounts of broken stone, particularly flakes, are the same type of stone as the outcrop

- identifiable stone artefacts, such as unfinished tools, hammerstones, anvils and grinding stones may be around the site

There are the scars on the outcrop where the rock has been removed – and there are also the chips of rock littering the ground under the scars – the remains of “processing” stone tools. Mostly these are just failed attempts at fashioning tools or simply off-cuts. It is very rare to find an actual intact finished tool at a quarry site. Often you will read about these off-cuts being described as “rock scatters” – and there can obviously be thousands of these chips in areas that stone tools were being manufactured.

One thing to note is that policy has shifted in recent years and stone tools are very rarely removed from a site and taken to a museum (they already have plenty in their collections). They are usually just buried in ground after recording – often tucked away somewhere a bit hidden like next to a tree stump if the tool was found right next to a walking track etc. The tools are part of a holistic archeological “site” rather than just an individual object. If you walk along a tourist track near rock you are very likely to be walking on or near Aboriginal “rock scatters”.

Some important things to note in the fact sheet:

What to do if you find an Aboriginal quarry? “Do not disturb the place or remove any material“.

It also says why they are important: “Aboriginal quarries tell us a lot about Aboriginal stone tools, provide a rare glimpse into the fabric of past Aboriginal society” etc.

We don’t question this – it is important to know where the stone came from, how tools were made, their link to other finds, the date of the sites and so-on. They are also obviously a fantastic link to the past for the Aboriginal community. Something as permanent as stone can last thousands of years – unlike wooden tools etc.

Arapiles’ quarries

In the latest round of bans announced by Parks Victoria they said this…

“Archaeological surveys have confirmed the Dyurrite Cultural Landscape is a place rich with cultural heritage including… one of the largest stone quarry complexes found in Australia.” – Engage Victoria website

Clarification – I think they forgot to put in a couple of words there – “largest pre-colonial stone tool quarry complexes found in Australia” is likely a more factual statement. We suspect many people unfamiliar with pre-colonial quarries in Australia may have a vision of something huge and imposing.

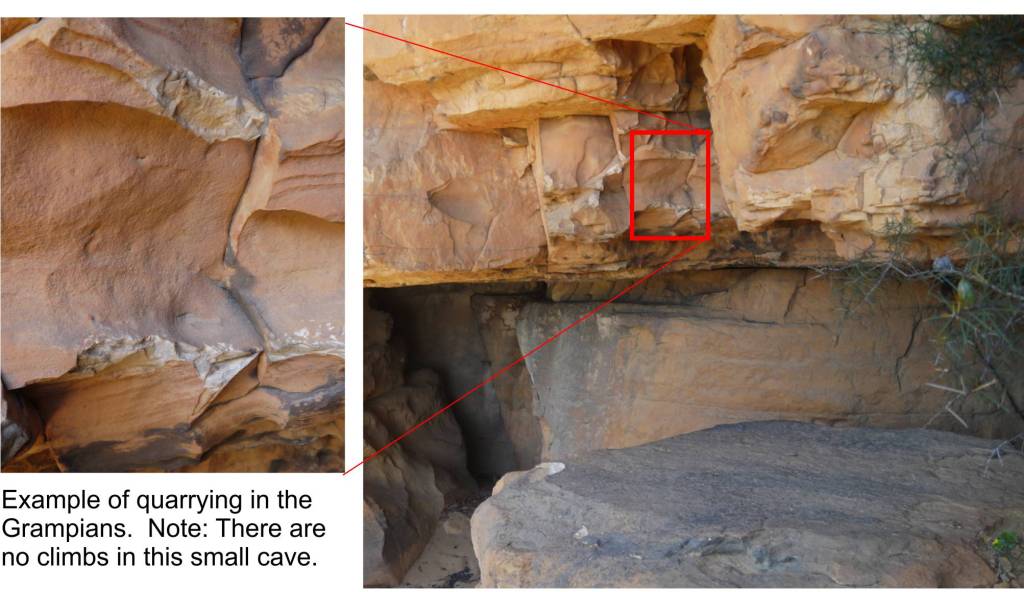

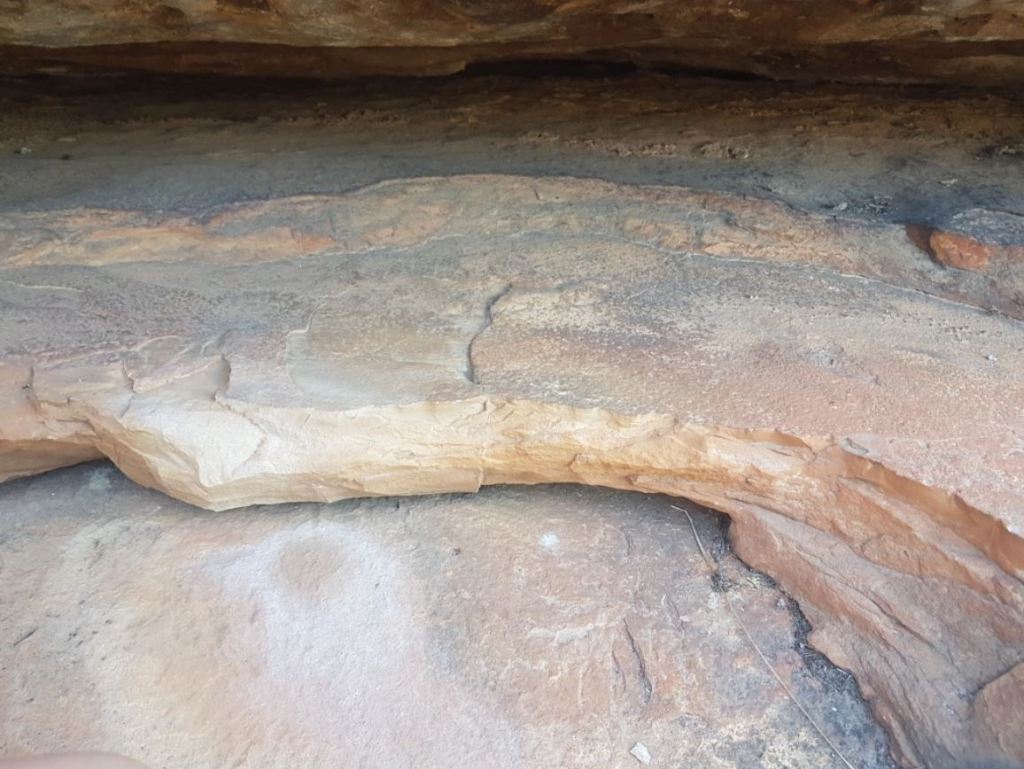

This is not what is being discussed here. Below is an example of one of the more extensive quarry sites at Arapiles – near the route Pilot Error. It appears a couple of kilograms of quartzite rock has been removed by smashing rock against rock along a natural rock fracture point. When Park’s Victoria and BGLC talk about quarries this is what they are talking about.

Other pre-colonial quarry sites in Australia

What are we comparing it to here? In this article the ABC claims “Australia’s Silk Road” is up in Queensland with claimed “200 quarry sites have been uncovered so far, with the largest containing 14,000 pits”. The article fails to show any photos beyond a scattering of small rocks on a plain. In NSW there is the Millpost stone axe quarry – there is an informative video on their website about how the axes were created – well worth a look. Closer to the Melbourne we have the Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry – (not to be confused with Mt William in the Grampians). This area is described as “Hundreds of mining pits and mounds of waste rock“. This area appears entirely off limits to the the general public with it being owned outright by the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation. Photos online show a couple of bits of knee height rock poking out of a grassy plain.

Arapiles is certainly a more impressive feature than that, but it’s the hardness and flaking qualities that are important – not the size of the mountain.

Dyurrite – one of the largest stone quarry complexes found in Australia?

In a Park Victoria’s press release about the Tiger Wall quarry discovery in 2020 they said:

“A vast stone-tool quarrying and manufacturing site of potential national significance has been identified at Mount Arapiles-Tooan State Park, in Victoria’s west.

The production site, which extends for around 200 metres around the base of a rock face, is where Traditional Owners – the Jadawadjali, part of the Wotjobaluk Nations – manufactured a variety of tools from stone sourced all over Dyurrite (Mount Arapiles). These included sharp-edged knives and spear-heads for cutting and hunting, and flat stones for grinding foods or crushing materials, such as to make pigments for painting.

The manufacturing site was also used to prepare the quarried stone for trade – stone from Dyurrite has been found throughout south-east Australia, part of the extensive Aboriginal trade network that existed prior to European arrival.”

So just how big are the quarries at Arapiles? The rock type is quartize, and is commonly found in the region, but while there are a lot of rocky overhangs, shelves etc at Arapiles (and nearby Grampians) – only the best bits seem to have been quarried – compared to the vast amounts of stone in the landscape. Indeed the recent book “Gariwerd – an Environmental History (which also mentions Arapiles) it says (P15) “Stone Tools were sourced locally, but lacked flaking qualities” It doesn’t go into detail, but compared to the Mt William quarries mentioned above, we suspect the claims might be more about the area that the quarrying is spread over, rather than the size of the sites themselves.

Even if only 10kg of stone was removed every year from the Arapiles cliffs over the last 3000 years (the shortest period of time we have read for occupation claims) we should see evidence of thirty tonnes of rock being removed. This is not what we see at Arapiles – it is of much smaller scale. The quarrying appears to be so minor in scale that no one seems to have noticed most of it until 2020 – and discoveries prior to that were only briefly mentioned in archeology reports.

The 1992 Arapiles archeology report

We’ll be referring to a document, Mt Arapiles Tooan State Park Archaeological Survey December 1992, a bit in this article. It appears to have been written as a public document, but these days it is relatively hard to access unless you live in Canberra or work within the Victorian government. No institution allows it to be removed from their collection on loan. We found a copy in the National Library but we cannot share the report in full here due to copyright restrictions. It contains an academic survey and assessment of the archaeological sites of Mt Arapiles.

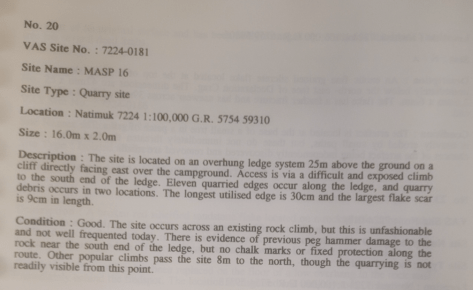

This survey lists 38 “sites” – with 10 being rock quarries and 13 being rock scatter sites. It also lists a couple of small art sites and 8 scar trees and a several other items such as unconfirmed water wells. So by far the majority of listed sites are directly involved with rock quarrying. Some of the listed sites are described as “minor and obviously a desultory attempt to obtain raw material“. Every attempt by someone to smash rock off an outcrop is recorded even if it was quickly abandoned as unsuitable.

While the latest surveys done in 2020 did uncover new, previously unknown sites, the majority were in fact already known about as a result of the 1992 surveys documented in this report. Local climbers such as Louise Shepherd were involved in the earlier surveys and took archaeologists to some hard to reach sites. It appears at the time that climbing and these sites were not mutually exclusive (more about this later). We do not have access to the 2020 report as it is kept secret as part of recent cultural heritage legislation – a problem that really hampers open and honest dialogue about these issues.

Are Aboriginal quarries under threat by climbing?

This is the big one – and it’s covered extensively in the archeological report from 1992.

“Quarries are not normally recognized as Aboriginal sites by the general public and are usually immune to vandalism. Being composed of rock, the quarries are also difficulty to either unintentionally or deliberately disturb or destroy.” – Mt Arapiles Tooan State Park Archaeological Survey December 1992

From the Victorian Government’s First People’s State Relations Fact Sheet:

“Human activities such as mining, road building, damming, clearing and construction can disturb or destroy Aboriginal quarries”.

No kidding – those are clearly destructive. No mention of recreational activities such as climbing or walking.

The location of most quarries at ground level – usually at a height that someone could sit and strike bits of rock off – means they are only briefly in the region where climbers operate. Bare hands and soft rubber soled climber shoes don’t damage rock that is being used to build hardy stone cutting tools (hint PV – we don’t use metal spikes on our shoes!). By their very nature rock quarries are places of solid rock – with the only way of removing the rock by striking it hard with another rock to split off a separate section to make a tool. This is not something climbers are doing.

The fact sheet also mentions “Natural processes such as weathering and erosion can also cause the gradual breakdown of stone outcrops“. Yes, in millions of years, those quarry’s won’t be there anymore – but neither will we.

Are Aboriginal quarries legally protected?

Again, from Victorian Government’s First People’s State Relations Fact Sheet:

“All Aboriginal cultural places in Victoria are protected by law. Aboriginal artefacts are also protected [meaning fragments on the ground]. It is illegal to disturb or destroy an Aboriginal place. Artefacts should not be removed from the site.”

Yep – all good. No disturbance. Ok, got it.

The 1992 Archaeological Survey is also revealing… in that it attempts to highlight any instances where climbers come into contact with and interfere with quarry sites – yet finds almost no cause for concern.

We know this because the report tells us in site by site detail:

Perhaps this is why, even after this report was produced, no attempts were made to protect identified quarry sites by removing climbers – because there was no “red flags” that were causes of concern. Damage hadn’t happened and that meant “no action is necessary”. The report talked of actions required to protect delicate art sites – and these included “concealment“, “monitoring“, and “protecting sites with a physical barrier“. This barrier is what was installed at the Cultural [art] Site next to the Plaque – and it worked – with climbers staying away since it was placed there.

In 2023, the ACAV also dived into the potential legal ramifications of climbers coming into contact with quarry sites, and is worth a read.

It would appear that the only “offence” that could be alleged by Parks Victoria would be disobeying park rules, as defined within the management plan (a plan, not an Act). Such an allegation would be open to challenge in the Magistrates Court in the same way a person would challenge an inappropriate traffic infringement notice

Anyway, where we go now is…

Misconceptions around climbing

Climbers “know” they aren’t damaging these sites, and this is acknowledged by PV (link to the Engage Victoria Community Information Session), that despite 60 years of climbers and hikers walking (sometimes over) quarry sites, they remain undamaged.

We’ll get to what has changed, but back to the actual survey there were indeed concerns raised about the possibly of harm to quarry sites, and it is raised thus:

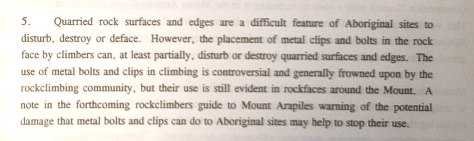

So the report does raise a concern about safety bolts – and it would be legitimate – if climbers placed safety bolts anywhere near quarry sites.

Firstly, the vast majority of climbs at Arapiles do not use safety bolts – instead they use “natural protection” which is removable and utilizes natural crack features and doesn’t leave permanent damage. This is the ethic of “clean climbing” in the community – and Mt Arapiles is our jewel in the crown of clean climbing in Australia. 99% of routes at Arapiles do not require safety bolts.

But if safety bolts are used – they wouldn’t conflict with stone tool quarry sites because they need to be installed at least three metres above the ground to be functional. Safety bolts are never placed at or near the ground, or eye level, or in fact anywhere you can actually reach from the ground. A ground level safety bolt has no use – it’s not going to stop a climber hitting the ground!

Safety bolts in general are not frowned upon – they are used where otherwise a fall might result in severe injury or death. Think about that. They are also used as a way of descent from the top of some climb features – often independent pillars with no walk off option – which is often a safer way of getting down, and reduces foot-traffic and erosion down more sensitive gullies.

In the 30 years since this archeological survey was published we’d be confident to suggest that no safety bolts have been placed near a quarry site as to impact any part of it. There is limited scope for any new climbs at Arapiles so new bolts are unlikely to be placed. We can be certain that any consideration for new climbs would factor in the location of nearby Cultural Heritage.

However, if you think that the survey authors from 30 years ago were unsure how safety bolts are used in the climbing community, they’ve got nothing on current PV executives (or possibly about to be ex-PV executives).

Despite GWRN’s best efforts to “assist TO’s to understand how climbing works“, and how we might use various spaces – we still have the perception (and a perception that is encouraged) that climbers bolt, chalk, and use “toe hooks” (not kidding) on Cultural Heritage. Their vision is one of a 1950s mountaineer banging in pitons and hooking up a cliff with ice axes and crampons. Back in 2019 when Summerday Valley was closed, PV staff were observed stating concerns about climbers using sledgehammers and generators, which is demonstrably false. Climbers don’t use those things.

Harm in the real world

The biggest threat to quarries would be PV infrastructure projects themselves that often involve chiseling stone steps into ground level rock slabs and installing handrails and metal ladders.

Another major source of potential harm to rock quarries would be bush-fire damage – either accidentally lit or lit as part of “proscribed burns”. Rocks literally explode or peel off like onion skins when exposed to high heat as trapped water in the rock expands to steam. We have seen this in full effect in the Grampians – especially around Hollow Mountain area with huge chunks of rock ripping off the wall.

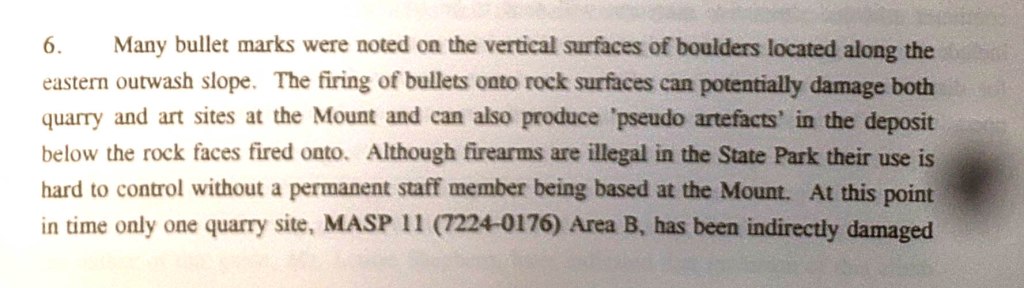

Has there been any recorded damage to quarries at Arapiles?

The only reference to any damage to a quarry site in the 1992 archeology report was noted as being created by bullets being fired at a shelter!

No attempts have been made by Parks Victoria to fence off any quarry site at Arapiles – and even now climbers continue to use many areas slated to be banned if the Dyurrite Cultural Landscape Management Plan Amendment is approved. Land managers know that climbers are not physically damaging these quarry sites.

Chalk and rockfall

In the 1992 archeological report chalk is mentioned in a few places – chalk was visible some metres away or above the quarry site. Even if chalk was inadvertently used on a quarried edge – common sense suggests that no harm is actually done. We’re not suggesting there needs to be NO concern – just that banning whole cliffs as a pre-emptive measure on the very small probably of a bit of chalk use is patently ridiculous (remember 95% of quarrying sites are not on actual rock-climbs – so chalk is a non-issue). The famous Gallery climbing area in the Grampians was banned because of a single “quarried” rock chip that was used as a climbing hold on Monkey Puzzle. The popular Spurt Wall warm-up boulder traverse has several ancient “chipped” holds that got a dab of chalk on them.

Chalk can be removed easily using water and a soft brush. It is not permanent and should not be treated as such. Check out this how-to guide here on the ACCNSW site.

Rockfall could damage quarry sites – but funnily enough it’s not mentioned in either the 1992 report – or indeed any recent communications from PV or BGLC. However, we have heard this being used as a reason why the act of climbing could harm quarry sites. The only thing is – that we’re not aware of any quarry sites being damaged this way. Arapiles is considered some of the best quality rock on the planet – rockfall is not normal or expected. There is a reason why school groups love climbing at Arapiles – rock fall is simply not a factor to be considered. Brains of alive human beings need to be protected as well!

We have been told by someone familiar with the survey’s that the Tiger Wall “quarry” may not actually be much of a quarry – instead it is supposed that it could be a site of “processing” suitable rocks, which were trundled off the top?! of the cliff and smashed onto the slab below – and then these smashed remains were further crafted into rock tools. It’s an interesting theory, but for starters, we have no idea how you would determine natural rockfall from deliberately thrown rocks – and also how you would determine recent rockfall vs pre colonisation rockfall.

In regards to any further potential rockfall, it’s important to note that the majority of loose or dangerous rocks that might have fallen from the cliffs have already done so in decades past (or been removed). There are very few loose rocks left on popular routes, and although the risk is not zero – it is also not zero if climbers are removed, as all sorts of things can impact rockfall – tourists throwing rocks, trees falling over near summits, rain and thunderstorms, and so on.

Sacred quarries?

There aren’t many sources making the claim that quarry sites are sacred. Blanket statements that climbers are “climbing on our Sacred Sites” are a bit disingenuous when the majority of closures to rock climbing areas are in fact due to quarrying.

Yes, they are protected under the Cultural Heritage acts, and should be kept in perpetuity, but sacred?

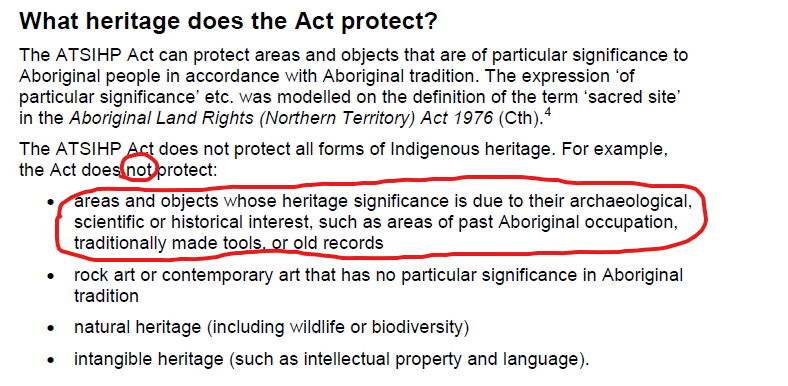

While the 1984 ATSIHPA (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act) is still a legal act – it is commonly referred to as “an Act of Last resort” – as it’s a National Act – and the State of Victoria 2006 Aboriginal Heritage Act is much more encompassing in it’s terminology and protections for Cultural Heritage (so the 1984 act is only invoked when States are dragging their heels on a contentious issue).

While the Vic 2006 Act doesn’t even mention quarrying, it does mention Sacred objects “Sacred, according to Aboriginal Tradition“. (P14)

Aboriginal cultural heritage means “Aboriginal places, Aboriginal objects and Aboriginal ancestral remains“. (P3)

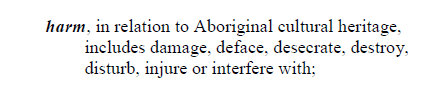

When it comes to “harm” the 2006 Act gives the following definition:

Note that the act was amended in 2015 to include “disturb” and “interfere with”. The explanatory memorandum specifically says this: “This is intended to assist in clarifying that collecting or removing Aboriginal objects from an Aboriginal places is an offence.” Yeah, not rock-climbers.

This kind of wording was required to prevent theft or collecting of rocks – and makes sense at places like Mt William (above) where you could (in theory) drive in and load up your car with quarried rocks.

Desecrate is an odd one – with religious overtones – Oxford says it means “treat (a sacred place or thing) with violent disrespect“. Quarries are unlikely to be “sacred” so again it doesn’t appear relevant but it is hard to judge what what person finds offensive in 2024.

We’re not suggesting the 2006 Act doesn’t or shouldn’t, apply to quarrying – but it’s wording is incredibly vague – so the smallest thing in the Act could lead to big access closures for all sorts of things. The majority of the 2006 Act tends to focus on Aboriginal Ancestral remains (big legal area), and construction / development of land – which inherently involves destruction of landscapes, mining etc.

Climbers are getting lumped in with high impact activities like land-development and mining – and that’s why so many climbers are voicing their opinions loud and clear on this issue. You can read about some of the regulatory burden that has been placed on Park Victoria’s operations in our 2020 article Parks Victoria Admits Heritage Regulations “Unsustainable”.

Proportional buffer zones?

So we know that climbing is highly unlikely to cause any damage to hard rock quarry sites – the archeologist report itself says this as does PV lack of physical barriers at quarry sites. But at the same time we see huge buffer zones put around previous climbing areas – appearing to close major cliff features like Tiger Wall and the Pharos. These same buffer zones don’t apply on walking tracks and roads on public land managed by Parks Victoria.

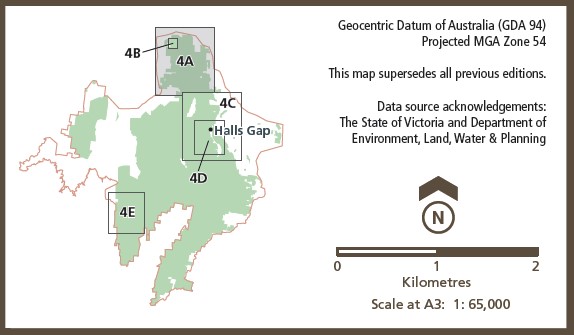

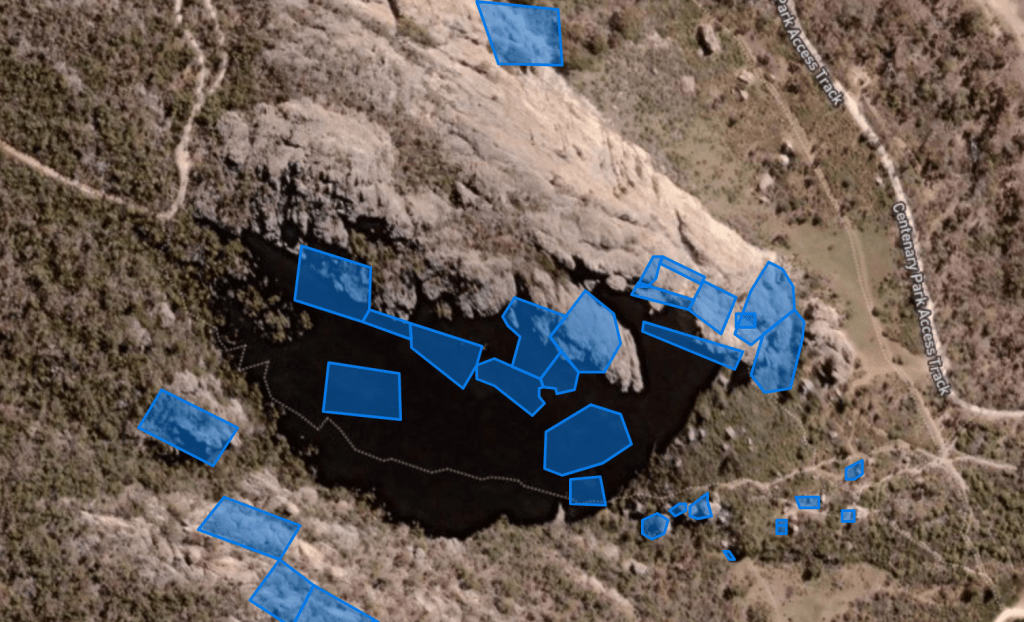

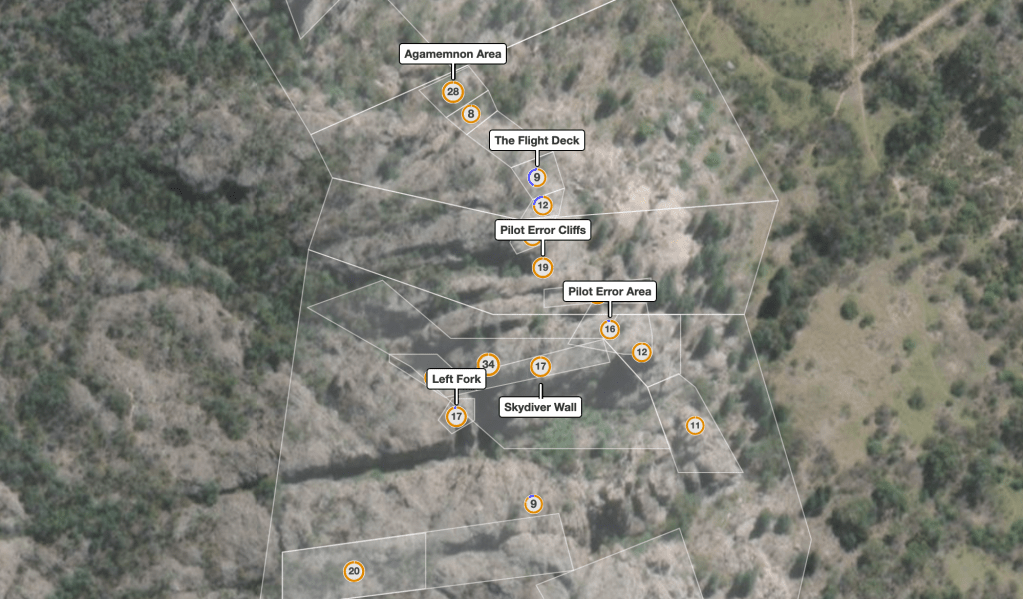

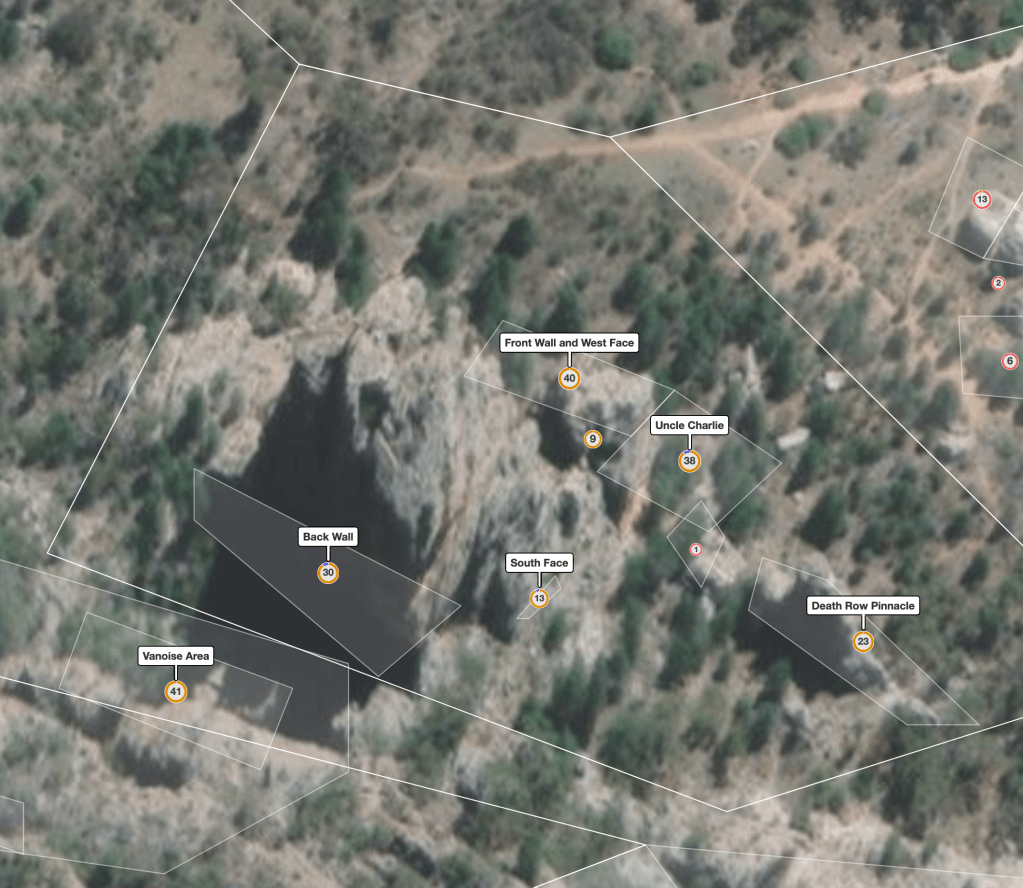

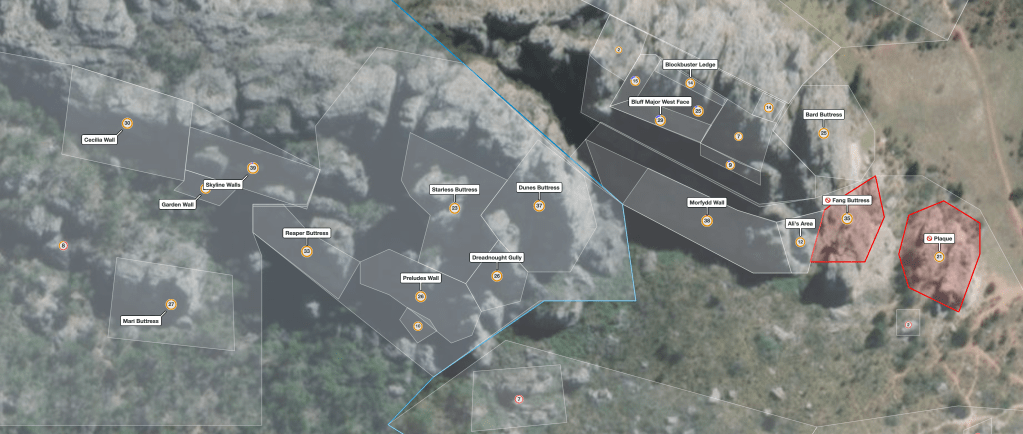

Thess area bans appears to be incredibly lazy management – using thecrag.com polygon mapping to restrict climbing access in an ad hoc way. The crazy thing is most of the polygon mapping of climbing areas on thecrag.com was not done by experts, or even locals – and it certainly wasn’t validated by any sort of official committee or anything. Official Arapiles guidebook authors such as Glen Tempest, Simon Mentz, Gordon Poultney and Simon Carter have never been involved in updating thecrag.com mapping. None of these people were consulted by Parks Victoria area closures either.

As a public “wiki” site anyone can just jump onto thecrag.com and draw a couple of lines around a fuzzy aerial photo that approximates a geological formation. When most of the mapping was done at Arapiles for thecrag.com by “Joe Public” more than a decade ago the online aerial photos were of terrible quality – very low resolution and often contained blurred glitches from poor photo stitching. They aren’t much better today when you take a look. These photos are updated every year – and often it means these polygon borders are now totally inaccurate. Often these climbing area borders cross another area into a mess of overlapping polygons.

Polygon “borders” of sites such as the Pharos are incredibly rough – but this is now taken as gospel by Parks Victoria as the border of each climbing area. If a small quarried rock feature strays into one of these loosely defined polygons – BANG – the entire area appears to have been closed. So one random person’s one minute approximate polygon drawn in the 2000s in Microsoft Explorer can shut a world class climbing area permanently. This is lazy management 101. We suspect someone back in the PV office didn’t even put boots to the ground when coming up with their mapping on what is open – or not.

And don’t forget when Parks Victoria claims half of the climbing areas at Arapiles will remain open – they are not comparing apples with apples. One “closed” area such as Tiger Wall can be massive – whilst an “open” area can be a tiny insignificant boulder sitting at the bottom of the cliff.

Unanswered Questions

In July 2022, The ACAV wrote a letter to Park Victoria’s Chief Conservation Scientist – seeking to clarify the issue of large area closures due to stone tool quarrying:

Park Victoria’s written reply was the usual formative letter that many have received over the last 5 years – entirely ignoring any of the detailed points in ACAV’s letter.

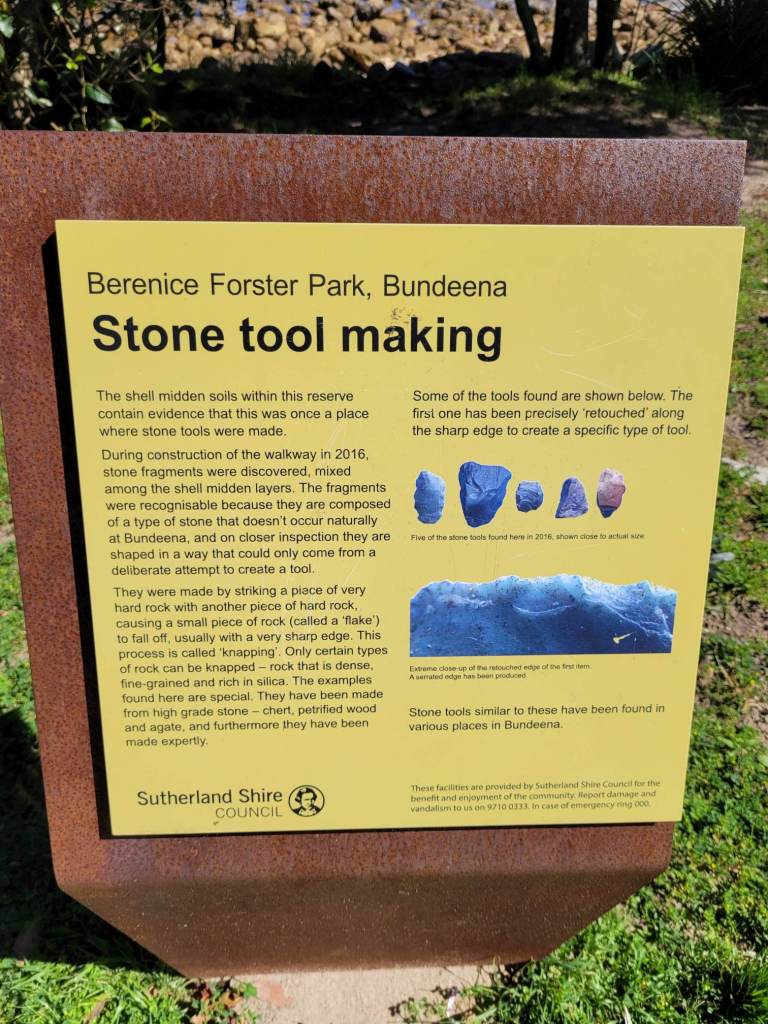

How are quarry sites protected elsewhere?

We mentioned in a recent article how even art sites could co-exist with recreational parks users – if given some space, signage and trust – rather than steel cages, but how are stone tool sites protected elsewhere? Here’s a sign for an area in NSW. Note – It’s not a quarry itself – but a toolmaking site, but does not say “no access”.

Even around Alice Springs – where the Arrernte people still live and have a deep continuing connection to Country – some sites (this is about 5km from town) just have a sign whilst access remains open to the general public. Respect and care – not exclusion, and this isn’t a quarry site – it’s a Sacred Site.

Quarries as tourism drawcards?

The Labor Allan government has been pushing the idea that “Cultural Tourism” could be a replacement for climbing tourism at Arapiles once they shut down half of the climbing. The location of the quarries at Arapiles and the small size of them means they are unlikely to be a tourist drawcard. There are equally as impressive sites an hour closer to Melbourne in the Grampians at pre-existing tourist areas such as Hollow Mountain – and these quarries are neither signposted or physically protected. It’s clear that Parks Victoria does not see any great tourism appeal from these areas. The press releases may call the Arapiles quarries as “one of the largest stone quarry complexes found in Australia” but this does not equate to something of broad public interest. As we write this it is 42 degrees at Arapiles – we can bet there is still a couple of dozen keen climbers out there on the rocks. Would any sane tourist drive 4 hours from Melbourne to look at rock chipped edges in the blazing sun? And what guarantee do we have that these tourists would behave appropriately around these quarries and look after them? We don’t believe there is any evidence to show they would be a superior “customer” than the rock climbers who currently consist of 99% of the visitors to Arapiles State Park.

Old quarries as climbing areas?

We would also like to point out the paradox that many of the most popular climbing areas in Australia are actually old colonial era rock quarries – for example Kangaroo Point is a 195 year old stone quarry that is now Queensland’s most popular climbing area. Perth’s premier outdoor climbing crag is Mountain Quarry, whilst Hobart has Fruehauf and Waterworks Quarry. No one seems to think climbing is incompatible at these areas despite significant heritage value to these places.

Moving forward?

Should long-known pre-colonial stone tool quarry sites justify fully banning recreational use of public land, even when no harm to the sites has been observed? That’s the key question.

We propose that both quarry sites and climbing could co-exist as they have done for many decades so far without harm being caused. Spread knowledge about the existence of these areas so climbers are aware of them. Close or redirect the start of specific routes if required. This was done successfully on the left side of Taipan Wall (let’s not talk about the right side…)

You know what type of quarry will radically affect the Wimmera landscape? The bloody huge mineral sands project approved by the Labor Allan government that is all over the news right now – 200 million tonnes will be removed. That’s the one we should all be fighting. What sums of money were paid to the Aboriginal parties to allow that mine to proceed?

Please share this article!

…especially with non-climbing friends when they ask, or assume that climbers are climbing all over Cultural Heritage and art sites.

Don’t forget to check out our 100+ other articles from the past 5 years about rock climbing bans on public land in Victoria.

Further reading…

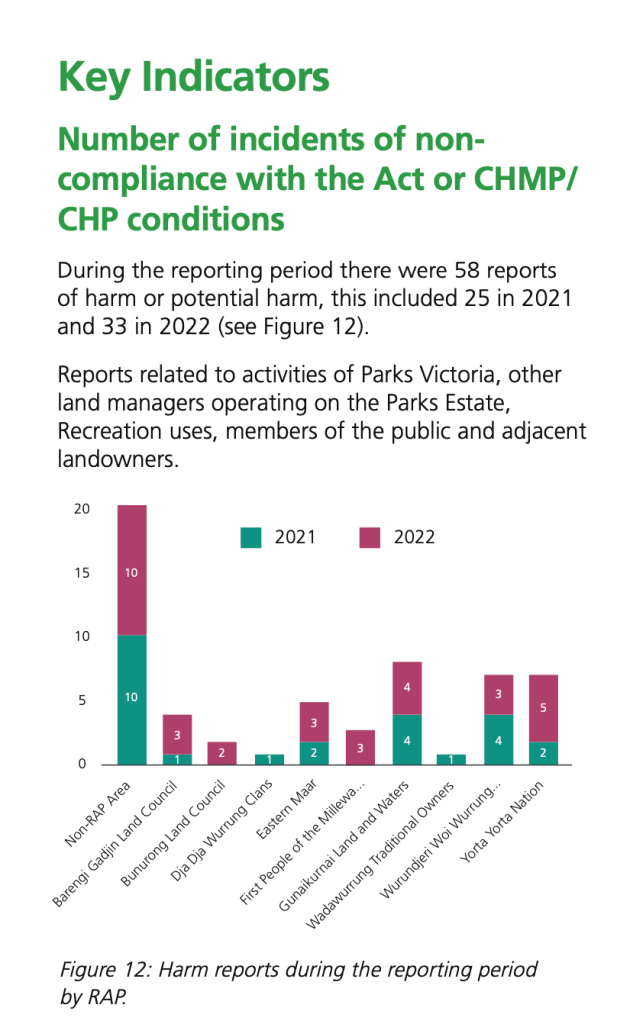

Want some “light reading” – take a look at these three reports from Parks Victoria and the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council about Cultural Heritage protection. It’s plainly obvious this is a huge bureaucratic monster and PV is having to hit KPIs after years of under performance in this field. We would hopefully do a deep dive on these documents soon.